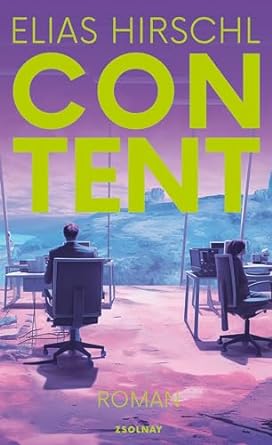

Recommended by New Books in German for translation into English, Elias Hirschl’s Content (published in January 2024) is a many-stranded satirical novel set in a dystopian near-future. Turning a critical eye on social media, content creation, start-ups and meaningless jobs, not to mention the rise of machines in nearly all areas of modern life, Content is a surreal caper through a deindustrialised landscape, by turns unsettling and hilarious. Elias Hirschl spoke to us about the novel, his creative practice and the future of writing.

Eleanor Updegraff: Content is an incredibly engaging novel: a wonderful satire that swings between moments of absurdity, poignancy and deep concern for the future. Could you tell us a bit about how the idea first came to you?

Elias Hirschl: I started back in 2020 during one of the Corona lockdowns. I started reading fewer and fewer books and consuming more and more online content, especially YouTube and Instagram videos, and then the book es fehlt viel [lacking a lot]by Katherina Braschel, in which the author writes partly about her own online consumption, gave me the idea of writing something along the same lines. I wrote a short story from the perspective of a woman who creates this kind of content in a content farm, like she’s on an assembly line, and that story slowly grew into a novel.

EU: So much of the novel is incredibly well observed – particularly the absurdities of digital content. Did you find yourself spending a lot of time online to research it?

EH: Well, yes, although it was more the other way round, in that I just started writing down everything I consume myself. When it came to things relating to TikTok, I always asked other people, because I didn’t – and still don’t – use the app myself. A lot is also based on how companies present themselves online, and I did on-the-ground research in the Ruhr in Germany for the whole coal-industry story.

Yes, I always enjoy writing books. But I always mix sad or scary moments with funny ones, because I think that’s just the realistic approach. In reality, sad and funny moments are always very close together.

Elias Hirschl

EU: Content is very entertaining but also quite disturbing, with a degree of anger or frustration below the surface. How did it feel to write it – was it fun or (also) worrying?

EH: Yes, I always enjoy writing books. But I always mix sad or scary moments with funny ones, because I think that’s just the realistic approach. In reality, sad and funny moments are always very close together. But I also made sure that there was a balance between good and bad. For example, in the novel the whole environment is collapsing; it seems as though the world is coming to an end. And so I made sure that at least the people who live in this world are all somehow kind to each other, because if things were also negative in a social dimension, then the whole mood [of the novel] would be unbearably pessimistic.

EU: One of my favourite storylines concerned the ‘Is It Cake’ era. From social media doppelgängers to office furniture made of cake, many things in Content are not what they seem. It’s a theme of your previous novel, Salonfähig [Socially Acceptable], as well – could you tell us a bit about this thread that runs through your work?

EH: Yes, they seem to fit well together: the way politicians or companies present themselves online and on stage. That facade that you, too, might build up for yourself on social media. The novel is very much about those moments when there’s a dichotomy between the self-portrayal of a thing or person and its actual essence. Is there even such a thing as an actual essence, a kind of core, or does there come a point when you consist of nothing but facades?

EU: Towards the end of the novel, the narrator quotes from Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, which also features a morally ambivalent narrator and a world in decline. To what extent did Musil’s novel inform your work?

EH: The novel influenced my work in that I tried to read it myself during the pandemic but just didn’t get anywhere with it. I still haven’t read it. The Austrian artist Julius Deutschbauer launched a project called the ‘Library of Unread Books’ a while back, and I think The Man Without Qualities was the most unread book, so I found this quite fitting. Also because it makes such a good counterpoint: this idea from the modern age of being able to depict the entire world in a single novel versus the completely fragmented nature of the internet.

EU: Content is set in a dystopian future, but many elements of it already exist in everyday real life. Can the novel be read as prophetic?

EH: Yes, the idea was more to include almost exclusively things that already exist today in one form or another. That’s why I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s a dystopian future, but more like a consolidation of many real things that do exist already, just brought together in a single place. There are private fire brigades in parts of the USA, for example, and there’s a mention of a Swiss start-up that wants to manufacture rocket-propelled delivery drones – that exists in real life, too.

EU: Social media seems to encourage us on the one hand to have a personal brand and voice, but on the other hand to create increasingly uniform content: a dichotomy that’s played out by listicle-writer Karin. As an author with a very distinctive style yourself, what does ‘voice’ mean to you, and is it a struggle to maintain?

EH: I think your own writing voice just develops by itself over the years; you realise then what you can do well and what not so well, and what you yourself enjoy writing. And above all, the more often you do it, the easier it becomes.

EU: Recently, there’s been a lot of debate about the role AI can or should play in the publishing industry and creative fields in general. As a writer and creator, what’s your view on this?

EH: I worry that it could lead to certain jobs being devalued. That, for example, a Hollywood company will have the draft of a new screenplay written automatically by a program, and the actual job of a screenwriter will then be downgraded to ‘and now make this manuscript look a bit prettier’, as it were. In other words, you’re really only doing editing and no longer the actual creative work. I see much less danger of this with novels, simply because publishers work differently. It doesn’t do me any good to be able to write faster or to write more novels, because publishers only want to bring out a new book [by the same author] every two years anyway. And the writing work itself is also the reason why I do it, because I just love writing as a process.

EU: You have a hugely varied career: you don’t just write novels, but also for theatre, radio and music, and you’re a prize-winning slam poet. How do these different practices influence one another?

EH: You learn a lot from each different genre that can be used in the others. In the theatre, for example, I learned a lot about writing dialogue, which in turn migrated into novels, and many years of experience on the stage have also led me to think about how a novel I’m writing will sound when it’s read aloud. And music is above all a conduit for everything, where you can just switch off without thinking too much.

EU: Can you tell us about anything you’re working on at the moment?

EH: I’m currently working on an older novel-in-progress again, and finally getting somewhere with it. But it certainly won’t be finished for a while longer. And I also keep working on a second album with my band Ein Gespenst [A Ghost].

EU: We’re always on the lookout for recommendations at NBG – any contemporary German-language authors we should be keeping an eye on?

EH: I would definitely recommend Selina Seemann (Die Stärkste unter ihnen [The Strongest Among Them]), Katherina Braschel (es fehlt viel [lacking a lot]) and Jimmy Brainless (Im Schein der Pfütze [In the Puddle’s Gleam]).

Upcoming bilingual reading and discussion:

‘Content’. A Reading and Discussion with Elias Hirschl and Ruth Martin, ACF London, 8th May 2024 at 7pm, more information here.

Elias Hirschl was born in Vienna in 1994, and he lives and works there as a writer, slam poet and musician. He won the Reinhard Priessnitz Prize in 2020. His novels include Meine Freunde haben Adolf Hitler getötet und alles, was sie mir mitgebracht haben, ist dieses lausige T-Shirt (‘My Friends Killed Adolf Hitler and All They Got Me was this Lousy T-Shirt’) (2016), Hundert schwarze Nähmaschinen (‘One Hundred Black Sewing Machines’) (2017) and most recently Salonfähig (‘Socially Acceptable’) (2021), published by Zsolnay.

Previous works: Salonfähig, Paul Zsolnay Verlag, 2021.

Find out more: eliashirschl.com

Author photo © Petra Weixelbraun

Eleanor Updegraff is a freelance writer, editor, and literary translator.

Her website is here: https://themonthlybooking.wordpress.com/about-this-blog/