NBG talks to translator Shelley Frisch about some of her recent translation work, including Kafka, Billy Wilder, and an Auschwitz survivor’s memoir

Hi Shelley, thanks for taking the time to talk to New Books in German! How are you? Where are you? And what are you doing at the moment?

Greetings from Princeton, New Jersey, and I’m pleased to be talking to you over at New Books in German! Our state of New Jersey is often associated with oil refineries and The Sopranos, but its slogan—The Garden State—certainly applies today. Everything is in bloom, and I’m enjoying bike rides along the canal, with delightful sightings of turtles lined up on logs, blue herons, and tiny chipmunks scurrying.

And today I’m feeling especially peppy, having just returned the page proofs for my forthcoming translation of Martin Mittelmeier’s Naples 1925: Adorno, Benjamin, and the Summer that made Critical Theory. The cover design is now out, as you can see, so I briefly thought of taking a little break from work, but here I am at my computer, writing up this interview. I’m making my way through a translation of a stellar new Hannah Arendt biography by Thomas Meyer, which brings in archival perspectives that deepen and expand our understanding of the evolution of her thinking and her practical work on behalf of the neediest refugees, to be published by Penguin. I’m also reading submissions for this year’s Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize—and what a treasure trove it is! I still plan to squeeze in a bike ride, though, particularly now that the rain has let up.

This weekend is also all about Princeton Alumni Reunions here, which means the streets and campus will be full of orange-and-black-clad Princetonians, some even sporting tiger tails. (Tigers are the school mascot, hence the color scheme. Full disclosure: I neither own nor plan to acquire a tiger tail.)

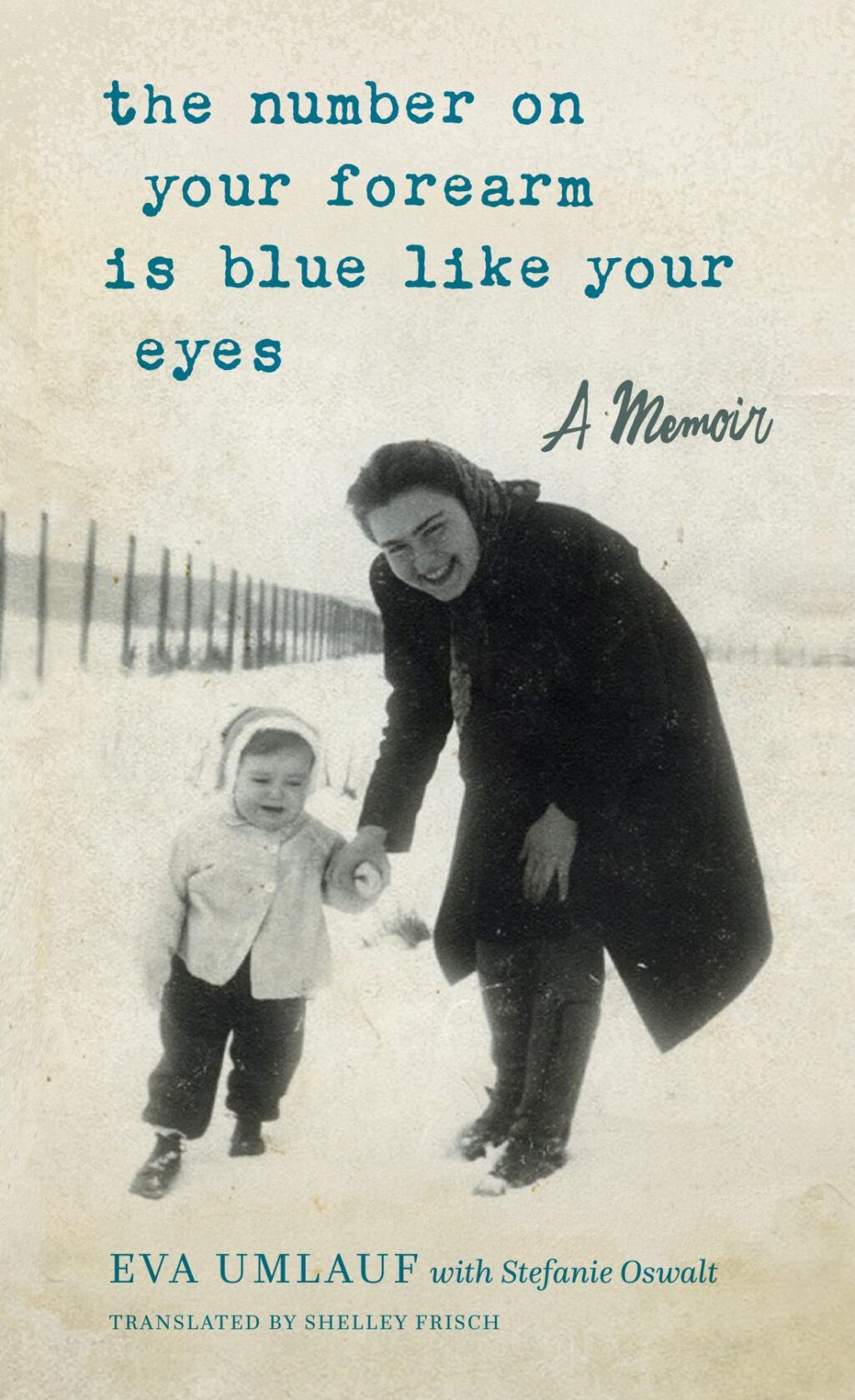

Your translation of Eva Umlauf’s memoir, The Number on Your Arm is Blue Like Your Eyes, is published on June 20th. A memoir like this of an Auschwitz survivor is a very special project to be entrusted with. Can you tell us a little about it?

This poignant and eye-opening memoir, co-published by Mandel Vilar Press and Dryad Press, is already out in the US, and we celebrated a beautiful book launch at 92NY in Manhattan two weeks ago. Eva Umlauf flew in from Munich to participate in our launch. Here’s an excerpt from the book description for the English-language edition:

On November 3, 1944, a toddler named Eva, one month shy of her second birthday, was branded prisoner A-26959 in Auschwitz. She fainted in her mother’s arms but survived the tattooing and countless other shocks. Eva Hecht was born on December 19, 1942, in Nováky, Slovakia, a labor camp for Jews. Eva and her parents, Imrich and Agnes, were imprisoned in this camp until their deportation to Auschwitz. A month prior to their arrival there, several thousand mothers and their children had been gassed. Now that the Red Army was rapidly advancing in Poland, the murders stopped. Agnes, then pregnant with her second daughter, and Eva were still alive when the camp was liberated on January 27, 1945. Her father was transferred to Melk, a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp, and died there in March 1945.

Eva, her mother, and her baby sister all survived (Eva’s father did not) and returned to what was left of their hometown. Eventually Eva married a Holocaust survivor who had settled in Germany, and she moved to Munich, with no knowledge of the German language. She had studied medicine in Bratislava, and little by little was able to establish a pediatric and psychotherapeutic practice in Munich. Now in her eighties, and a vibrant and utterly delightful person, Eva Umlauf continues to help patients cope with trauma, and she gives lectures about the Holocaust and its ongoing significance in Germany and throughout Europe.

This book project has been quite special and personal for me, as the daughter of a refugee from Germany. Eva’s memoir is like no other, in part because she has no direct memories of her experience in Auschwitz, yet she bears the trauma (and the number on her arm) of having lived through it. I wept while translating it, but Eva’s survival and brilliant postwar life story is an uplifting testament to the human spirit. I’m so pleased that it is slated for UK publication this June.

I wept while translating it, but Eva’s survival and brilliant postwar life story is an uplifting testament to the human spirit.

Shellley Frisch

You had a sold-out event on Billy Wilder at the Neue Galerie in New York earlier this year. He’s a fascinating figure and I know I know you translated some of his journalism. Could you tell us a little bit more about the evening and about the book you translated: Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna?

What a joy it was to translate this book (for Princeton University Press)! I got to work alongside Noah Isenberg, a film scholar (and recovering Germanist), who had discovered two volumes of Billy Wilder’s early journalism (when Billy was still “Billie,” though his actual name was Samuel, but that’s a story for another day…), one from Austria and the other from Germany. Noah and I had a grand time selecting a set of deliciously chuckle-inducing pieces for the volume.

Permit me to pull out an excerpt from my Translator’s Note for the book:

We sought out a selection that would offer readers a sweeping overview of Wilder’s reflections on current films, the latest cultural and fashion trends, fickle weather patterns, his own plans to shoot a film—and how that film evolved—and his encounters with both celebrities—Ernst Lubitsch, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Asta Nielsen, Paul Whiteman, the Tiller Girls—and a whole host of quirky “ordinary people,” such as the lucky (real or imagined) individual who earned his living by smiling uninterruptedly. Wilder’s range is vast: we learn how the smell of matches has evolved, how efforts to modernize cafés wind up erasing our collective memories, how a business tycoon can’t manage to see a dentist, how the Prince of Wales suffers from an absurdly privileged ennui, how the art of telling lies ought to figure in the school curriculum… And we learn, in two pieces about Wilder’s work as a dancer for hire, how that humble job opened the door to his pursuit of journalism.

His essays engage and quicken our senses, as Wilder’s “eager nostrils” chase down scents or as he brings musical life to inanimate objects, such as in this passage from “Renovation, an Ode to the Coffeehouse,” which infuses the atmosphere of a café with the tones of what Wilder calls the “molecular miracle” of “metaphysical ensoulment”:

Coffeehouses have something in common with well-played violins. They resonate, reverberate, and impart distinct timbres. The many years of the regular guests’ clamor have stored their filaments and atoms in a singular way, and the woodwork, paneling, and even pieces of furniture pulse marvelously to the tunes of the visitors’ life rhythms. Malice and venomous thoughts of a decade on the blackened walls have settled in as a sweetly radiant finish, as the finest patina. Every sound, emanating from the faintest quiver, the most unremarkable brains, comes through and runs endlessly, in mysterious waves, across all the molecules of the magnificently played sound body, day after day,…

Wilder’s prose is, well… wilder than I usually get to render in my translations. Where else do I get to write about “witless wastrels,” about an Englishman “blessed with hearing like a congested walrus,” about a performer with “gasometer lungs,” or a smoker who can “make his pipe saunter from one corner of his mouth to the other”?

The evening at Neue Galerie was splendid—a full house at a jewel of a museum. Noah and I savored the opportunity to revel in Billy Wilder’s cinematic prose once again. This volume has now been translated into several other languages, most recently into Chinese!

You won the Helen and Kurt Wolff Translator’s Prize a decade ago for your translation of Reiner Stach’s Kafka: The Years of Insight. As we approach the 100th anniversary of Kafka’s death, Reiner Stach participated in the parade of German authors at the Turin Book Fair in May. Kafka is also the subject of a six-part TV drama series by ARD, directed by David Schalko, which will come to Walter Presents and other streaming platforms later in May. The UK’s Guardian newspaper quotes Daniel Kehlmann as noting that Kafka was ‘one of the first writers of the 20th century to recognise bureaucracy as a phenomenon of almost existential gravity’ and that he understood that ‘our lives are entangled in a system we no longer understand. But he understood it because he was a bureaucrat himself’. What do you think is behind the enduring interest in Kafka?

Kafka was not an otherworldly, head-in-the-clouds fiction writer, but someone firmly anchored in reality.

Shelley Frisch

I should start by saying that “The Years of Insight” was one volume of a three-volume biography of Kafka. (“The Early Years” and “The Decisive Years” are the other two.) In all, the biography runs to some 1800 pages, so it was quite a deep dive for Reiner, and then for me! Luckily, I’ve been fascinated by Kafka throughout my adult life, and doubly lucky because Reiner’s prose and narrative prowess made the biography a stylistic joy (and challenge—I tried to be as “Stachian” as I could!) to translate, as well as a triumph of Kafka research. There was Reiner’s voice to translate, and there were the voices of Kafka: Kafka as storyteller, Kafka as diarist, Kafka as letter-writer… Kafka’s reluctance to publish his works—and in the case of his three novels, even to complete them—is yet another complicating factor. In recent years, the question of who “owns” Kafka has been played out in court (see Benjamin Balint’s riveting depiction of this issue in his recent Kafka’s Last Trial: The Case of a Literary Legacy). Kafka ultimately belongs to all of us but to no country.

I’m pleased that you cited Daniel Kehlmann’s comment about bureaucracy. Daniel wrote the screenplay for this TV series in consultation with Reiner, and his comment highlights a key point that runs throughout the three-volume biography: Kafka was not an otherworldly, head-in-the-clouds fiction writer, but someone firmly anchored in reality. His day job, as a lawyer assessing accident risks in the workplace, brought him into contact with people from all walks of life (including those whose accidents prevented them from actually walking), and with countless maimed and shell-shocked war veterans. The bureaucratic hurdles he encountered in his professional life profoundly shaped his fiction.

I should add that I have continued to work with Reiner on Kafka—neither one of us can let go of our abiding interest! Two years ago we published a volume of Kafka’s aphorisms that features the aphorisms themselves in both the original German and my translations along with Reiner’s extensive and thought-provoking commentary. Who knows—might we have more Kafka projects down the line?

Why the enduring interest in Kafka? I would assume that readers from around the world find, as I have, that his stories tap into deep-seated fears and anxieties. There are no happy endings here (indeed, Kafka never completed any of his three novels), but the universality of his themes resonates with anyone, across cultures and languages, who has sensed that our world is out of joint, and that we ourselves are out of joint within this out-of-joint world.

Shelley Frisch is an award-winning translator of numerous books from German, including biographies of Nietzsche, Einstein, and Kafka. She lives in Princeton, New Jersey and holds a doctorate in German literature from Princeton University.