Shaun Whiteside looks at how the idea of the German Democratic Republic continues to inspire writers and readers.

It’s thirty-five years since the Berlin Wall came down, long enough for some of the clichés of East Germany to be dispelled or overcome – there’s more to the GDR than dour border-guards, comical pedestrian-crossing figures, phone-tapping and terrible coffee. The idea of the German Democratic Republic continues to inspire writers and readers, and many of the books published recently on the subject have attracted the attention of prize juries.

Katja Hoyer’s magisterial history Beyond the Wall, noted for its generous reappraisal of life in the East German state, was long-listed for the 2023 Baillie Gifford Prize. In it, Hoyer deliberately goes beyond received opinions about the GDR, emphasizing the possibilities for individuals to attain a degree of self-expression. ‘Die Wende’ – ‘the change’ – should, she stresses, be seen as process rather than event; a change in consciousness, not just in political borders.

Katja Oskamp’s Marzahn, Mon Amour, the fictionalized memoir an author turned chiropodist in an eastern suburb of Berlin, was a justified winner of the 2023 Dublin Literary Award in Jo Heinrich’s razor-sharp translation. Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos (brilliantly translated by Michael Hofmann), the story of a young woman’s affair with an older academic, played out with a marvellous degree of nuance against the end of the GDR, won the 2024 International Man Booker.

The previous year, Clemens Meyer’s While We Were Dreaming, in Katy Derbyshire’s outstanding translation, related the experiences of three more-or-less oblivious unruly teenagers around the end of the GDR; it was short-listed for the 2023 International Man Booker. Lucy Jones’s splendid translation of Siblings, Brigitte Reimann’s study of divided loyalties on either side of the Wall – originally published in 1963, and with end-notes by the translator that almost constitute a small work of their own – was also enthusiastically received by critics and readers, and conveyed a sense of the fierce loyalty felt by some to the politics and lifestyle of the Communist state.

Poet and novelist Lutz Seiler, author of the prizewinning Kruso has denied that he is writing about the East German state as such, more about a specific time and a specific place. His poems in Pechblende, translated by Stefan Tobler as Pitch & Glint, address the devastation caused to his home village by Soviet uranium mining. His novel Star 111 – like Kruso, expertly translated by Tess Lewis – is an exploration of the anarchy that followed immediately on from the fall of the Wall. It has been touted in some quarters as the Wenderoman – the novel of ‘die Wende’.

In their different ways, all of these books open up different perspectives on life beneath the s, also probing how their consciousness and sensibilities were moulded by that system.

Three and a half decades on from the events of 1989, the memory of the GDR remains a rich seam for German writers, as evidenced by a raft of recent enthralling publications. Some approach the topic obliquely, to avoid the perils of the well-worn path, or the straitjacket of the western perspective. Others view the state from a more direct perspective Drawing topics from the recent past can also lead to controversy.

Matthias Jügler’s taut thriller Mayfly Season, shortly to appear in English translation by Jo Heinrich, addresses the question of forced adoption in East Germany. Hans and Katrin, a young couple are told that their son, Daniel, has died a day after his birth. Post-unification, after Katrin’s death, and when access has been granted to the GDR’s archives, Hans decides to look into the issue again. After attempting to examine his files they discover them to have been heavily redacted. Further research reveals that the child was living with an adopted family, and contact is made, only to be broken off again. The novel has proved highly contentious (leading to the cancellation of a reading, for example), with politicians disputing that any such cases existed, while dedicated pressure groups insist that such adoptions occurred on a huge scale and can produce personal evidence to suggest that they did. The trail of controversy has long outlived the state.

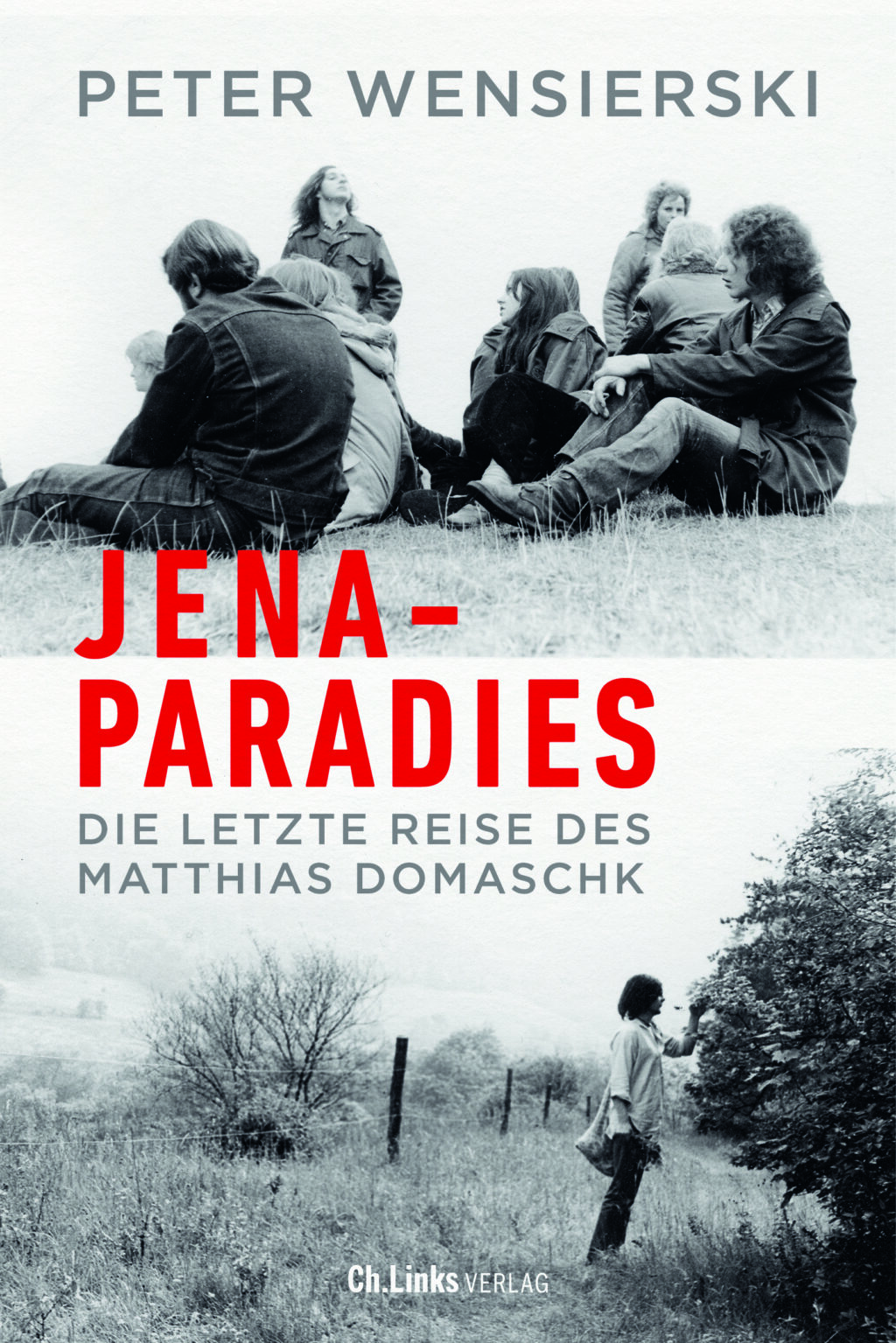

In his investigative study Jena-Paradies. Die letzte Reise des Thomas Domaschk (The Last Journey of Thomas Domaschk), award-winning writer and documentary-maker Peter Wensierski presents us with a more familiar vision of the surveillance state, vividly relating the final days of a young dissident in the East German city of Jena in 1981. Using hundreds of interviews and eye-witness accounts he creates a picture of a generation, no longer willing to accept a totalitarian state as its parents had done, and prepared to risk death to challenge it.

Matz, as he was known to his friends, is a music fan (the narrative is peppered with song lyrics), the ‘decadent’ son of the deputy director of Jena’s optic works, long-haired and hence one of those likely to attract the attention of the over-enthusiastic Stasi, and an occasional poet. The tale builds slowly, accumulating details of dozens of proliferating dissident groups, some quite hardcore, some less so, but all evidence that the state was on the brink of collapse. It paints the picture of a proliferation of angry and lyrical youth subcultures that could no longer be contained. The circumstances of Domaschk’s death in police custody have never been determined; this evocative account paints a grim picture of the surveillance state, and a rich portrait of the marginal figures that helped to bring it down. The book will appear in translation by Jamie Bulloch, published by MacLehose Press.

Less directly, the brief, almost pointillistic reflections of poet and psychotherapist Helga Schubert in Vom Aufstehen (On Getting Up) reconsider the nature of the state in which she lived after the war. It’s plain that she matured in an intellectual tradition very different from the western one. ‘Anna Seghers is supposed to have said that it takes about fifteen years as a writer before you can tell the story of a major event in a literary way.’ Schubert was known for her stories of everyday East German life seen from a woman’s perspective.

Now writing in her eighties, she reminisces about the special privileges she was granted as an author – she writes of visiting the Wall from the West, and realising that it was West Berlin that was enclosed, not the East. And yet she returned: ‘How can I make them understand that I feared the system in the GDR and still went back behind the mine-belt?’ Even as a psychotherapist – not a profession one often associates with the intellectual life of East Germany – she seems a little uncertain as to why, and yet of course it was home. Her writing describes an internalised struggle that even now seems unresolved.

The author Judith Kuckart grew up in the Rhineland, but has long had a fascination with life in the East – as a dancer in the 1980s she developed a piece called Kassandra based on Christa Wolf’s writings – and touches on the subject again in her quirky novel Café der Unsichtbaren (Café of the Invisibles). Not a café, in fact, but a Samaritans-style telephone counselling service for the lost and lonely of Berlin.

With unmistakeable echoes of Marzahn, mon amour, Kuckart’s novel examines the lives of those left behind by a success-based society, and the people who try to help them: Matthias, whose father committed suicide, and who has bought himself an apartment that he can’t afford to furnish; Rieke, a theologian using the listening service to train for pastoral care; and perhaps most importantly in this context Wanda, who grew up in the East, but when it was no longer the Democratic Republic (a ‘Zone child’, as she calls herself) and has a heightened sympathy for the left-behind as a result. Wanda works in the store of a museum devoted to GDR memorabilia, suggesting that this historical phase is fading into the past, to be packed away and essentially forgotten, like the bewildered East German callers she talks to. This is a different take on the East – Germany has moved on before its new citizens have really grasped what’s happening – which might also help to explain the country’s present political divisions.

Another novel – a highly readable one – that has raised critical eyebrows is Charlotte Gneuß’s Gittersee, a tale of love, manipulation and revenge set in a small town in East Germany in the 1970s. The author grew up in the West, and was born after ‘die Wende’, so obviously cannot have experienced life in the GDR. Furthermore, her fellow-author Ingo Schulze, who was growing up in Dresden at the time described, has spotted a number of errors in the book, which may or may not be changed in future editions (the river Elbe, for example, was so heavily polluted that a character swimming in its waters would have been unlikely to emerge alive).

The controversy surrounding the book raises big questions about authenticity, cultural appropriation and what topics are out of bounds for authors. In Gittersee, seventeen-year-old Karin, known to her friends as Komma, is in love with the clever, sensitive, motorbike-riding Paul, who disappears one day, perhaps to the West. Rumours reach Karin that he may have been killed, and suspicion falls on the local Stasi officer. It’s a clever book with a twist, and it does inevitably prompt discussions about which topics may be off-limits for writers in future.

As the years advance and the fall of the Berlin Wall recedes into the past, the literary response to the GDR will no doubt continue to metamorphose in all kinds of unpredictable ways. For now, once written off by commentators as ‘a footnote in world history’, it has emerged an abundant source of thought-provoking material for authors, and looks likely to do so for some time to come.

Recent NBG jury picks that are concerned with the GDR:

Shaun Whiteside photo above © Camilla Pastorelli

Shaun Whiteside is a literary translator. Originally from Northern Ireland, he graduated with a First in Modern Languages from King’s College, Cambridge, and translates from German, French, Italian and Dutch, having previously worked as a business journalist and television producer.

His translations from German include works by Freud, Schnitzler, Musil and Nietzsche, and more contemporary authors, including Luther Blissett/Wu Ming, Charles Lewinsky and Judith Schalansky. His work has earned him the Schlegel-Tieck Prize, and he has been shortlisted for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. He is a former Chair of the Translators’ Association.